“Every political, corporate, and educational leader who wants every youth to learn the same material at the same time as every other youth is an obstacle to the evolution of our species that our times demand.” — David Marshak, Inviting Youths to Claim the Power of Their Imaginations

Today many families are facing the question: What is learning? We eavesdrop on our childrens’ flat and chaotic Zoom experiences and we wonder: is this learning? Hmm. We may feel they are actually learning more in activities we would have previously classed as “mere play.”

I witnessed this firsthand. My nephew had finished his first grade Zoom “morning meeting” — an assortment of silly singsong greetings and technical problems — and was given a short break before his next “class.” This was just enough time to dive into a flow state with his elaborate Lego project — building new towers, connecting sections, dramatizing scenes between characters. As he was told he must stop and return to class, he yelled: “I hate learning! I hate learning!”

That week, I’d seen this child eagerly practice adding fractions while we were making banana muffins. He’d hand-written a sweet birthday letter for my dad. He’d begged for more time to practice his piano chords. He had thoughtfully taken in the difference between solstices and equinoxes when we discussed them over dinner and explained this to his younger brother the next morning. He’d asked questions about carbon emissions caused by cars. He was teaching his baby sister how to use a finger labyrinth. He loves learning.

His expensive private school was aware of none of these things. In the meantime, it was teaching him that learning was something completely different. Something really, really boring.

What is learning? How does our mindset and deep beliefs about learning constrain the experiences we create for our children?

Two metaphors for learning create two different realities

The tour-bus metaphor

A “tour-bus” metaphor seems to underpin our cognition of how learning works in a deep way. Think of the last time you were on a tour-bus. It may have been a tour bus while visiting a new place, or a bus ride as part of an amusement park.

Now, think about the last class you took — either in person or online. Just like a tour bus leader, you’ll hear the teacher say:

“Here we go!” or “Let’s get going!” at the beginning

“Let’s move into..” “Let’s get back on track” “We need to move on” in the middle

“We’re winding down” “We’ll stop soon” at the end

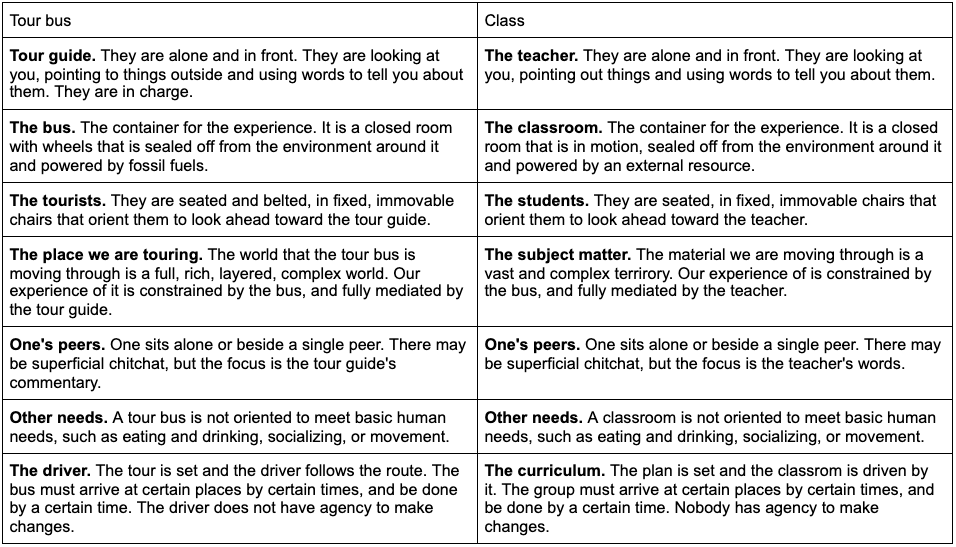

Let’s unpack the ways tour bus rides are similar to conventional classes:

The tour-bus metaphor is one instantiation of a deeper supermetaphor, LEARNING IS TRAVEL specifically, a form of travel in which a group is being driven in a moving vehicle. This structures our understanding of learning and how we think about it.

It is the reason why we worry about our kids being “behind,” why we want to be sure they are “on track,” why we want to be sure their learning is “going in the right direction.” Here are some of the entailments of this metaphor:

Everyone needs to go to the same place.

Everyone needs to get there the same way.

Everyone needs to arrive at the same time.

When the next bus is coming is unclear.

If you miss the bus, you may be at a disadvantage, because others are getting there in fuel-powered vehicles and you can only get there using your own energy.

If you get behind, it is hard to catch up. You may not even be able to catch up.

You may be late. You may not get there in time. You may miss the thing everyone is after.

And, further, this metaphor is elaborated by our understanding of lateness. Generally, as a culture, we believe the following things about lateness:

People are unsympathetic towards late people.

Late people are irresponsible.

Being late shows disrespect or bad character or bad upbringing.

Systems are not designed to accommodate late people and rightly so.

Late people have fewer options and benefits.

If you are late, all the good things may be already finished.

Late people are never successful.

Late people miss opportunities and can never get them back.

If you are behind, you won’t be part of the group where all the value is created.

The metaphor of LEARNING AS A MOVING VEHICLE is incredibly pervasive. Our culture has even conceived (and named) entire pieces of legislation based on this misguided and incomplete mindset toward education. Combined with our folk understanding of how bad lateness is, parents become very worried about their kids “missing school.” It may be helpful for parents to realize that the metaphor isn’t the reality.

There are many kinds of learning, and there may be a few for which the tour bus provides a useful metaphor — for instance, when a group of people are seeking efficient, superficial contact with a domain that is completely new to all of them. However, many kinds of learning require deep, tactile engagement with the world and ones’ peers, an individually-paced process, creativity and co-creativity, and other freedoms that the tour bus metaphor renders invisible.

The labyrinth metaphor

Have you experienced a walking labyrinth? A labyrinth is a single long path that has been folded many times to fit into a circular shape. The dimensions of the path and the nature of the folding have been optimized over hundreds of years to catalyze a mood of presence and alertness in the walker. Labyrinths have spontaneously arisen independently from one another in a variety of different human cultures, suggesting that they represent an archetypal form for humans.

Here is a typical experience of a labyrinth: An individual is free to choose if, when, and how to enter the labyrinth — or not. One individual enters at a time. They walk to the labyrinth’s center in whatever speed or manner they choose, and then, when they are ready, they return. If this is a group experience, there may be a facilitator who holds space and orients participants to the labyrinth. When others are present, there are many different ways one might encounter them. Many people report having deep and sometimes transformative insights in a labyrinth walk.

I see the labyrinth as a more relevant metaphor for a learning experience than the tour bus. It provides a template for agency, non-coercion, rhythm, groundedness, and individual process.

Let’s unpack the ways labyrinth walks can function as template for self-directed learning experiences:

I ask you to consider how different these journeys are — the journey of a tour bus and the journey of a walking labyrinth. When you think of things YOU want to learn, which kind of journey would you prefer? Why do you think that is?

If you are a learning experience facilitator, how would what you offer change if you let the metaphor of the labyrinth guide your relationship with learners and their relationship with the content, experience, and one another? Are there other metaphors you feel might better highlight what you see as the key dimensions of learning? To explore how metaphors work more deeply, I encourage you to read George Lakoff and Marc Johnson’s seminal work Metaphors We Live By; I’ve drawn from their approach in doing the above analysis.

What’s Next

If you are a parent, can you spot the tour buses your children are on? Seeing them, and noticing the superficial ways in which they engage, is the first part of the change process. The next step is to begin the process of exploring self-directed learning. They are many wonderful resources online, such as the podcast Honey, I’m Homeschooling the Kids! and the incredible film Class Dismissed.

My nephew is resilient. He will continue to love learning, regardless of what he calls it. The pathetic video meetings that his school was able to effortfully muster for him during COVID will quickly pass into oblivion. He will know that learning is life, and life is learning, and he will go on to create, discover, and express himself joyfully in many ways, enriching his mind and body and those of everyone around him in the process. What makes him so resilient? I like to imagine that he, and each of us, has a relationship with a learning spirit that guides our labyrinthine learning paths.